From the European Province Archives

22 November, 2021

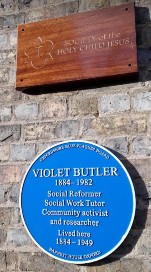

On Friday 29th October, a blue plaque celebrating the life of Christina Violet Butler was unveiled on the front of No. 14 Norham Gardens. Violet Butler was born and spent much of her life until the year 1949, at the property now home to the Norham Gardens Community of the SHCJ. On the same afternoon, the plaque commemorating Grace Hadow was also revealed at 7 Fyfield Road.

On Friday 29th October, a blue plaque celebrating the life of Christina Violet Butler was unveiled on the front of No. 14 Norham Gardens. Violet Butler was born and spent much of her life until the year 1949, at the property now home to the Norham Gardens Community of the SHCJ. On the same afternoon, the plaque commemorating Grace Hadow was also revealed at 7 Fyfield Road.

Many gathered at the ceremony including the members of the Norham Gardens SHCJ community, representatives of St Anne’s college and Violet Butler’s family. After a fascinating account of Butler’s life given by Dr Liz Peretz, Butler’s nephew Sir David Butler, shared his memories of the loving aunt who had supported him during his undergraduate days and was kind to all. An academic whose field was, quite literally, ‘the wants of the age’, it is most fitting that Butler and the Society should be connected to one another.

Butler read modern history as a student member of the Society of Oxford Home Students, the same Oxford institution under whose aegis the SHCJ’s Cherwell Edge operated as a hostel for female Catholic students of Oxford. She came from a family of academics and social reformers, her father was a fellow of Oriel College and her sister Olive worked at the LMH Settlement in London. Another sister, Ruth, taught at the OHS along with Butler herself while their brother Harold was a classical scholar. The famous campaigner Josephine Butler was an aunt by marriage.

Obtaining a first-class degree in 1905 and becoming the first woman to gain a distinction in the Economics Diploma in 1907, at the age of 28 Butler completed her book Social Conditions in Oxford. This was a detailed analysis of the lives of working people and provision for the poor. Unlike other social scientists of the day, Butler’s study was based on investigative work that she had carried out singlehandedly. To gather information for her chapter looking at the work of men and boys in Oxford, Butler interviewed over 400 teenagers and their families to learn about their experiences.

Much like the foundation of the SHCJ’s work in Preston, the first sisters came to Oxford at the request of a Jesuit Priest, Father Walter Strappini, to teach in the mixed infants and girls schools of St Aloysius Parish. The SHCJ began teaching on 19th October 1902. By the time Violet was making a survey of schools for her book, the SHCJ’s work in the parish schools was well established. Mother Mary Agnese Duckett and Mother Margaret Mary Greene served as headmistresses from 1902 to 1910 and 1910 to 1922 respectively.

In 1904, the Oxford community moved from St Clements to South Parks Road where their new ministry managing a student hostel was to begin in 1907. This venture did not interrupt the SHCJ’s work with the children of St Aloysius’ Parish. On the contrary, several of the SHCJ studying for Oxford degrees worked at the school as unpaid helpers such as Sister Mary Genevieve France and Sister Mary Bernard Coupe. As Catholic education progressed in Oxford, the SHCJ based in Norham Gardens not only continued at the Parish School – renamed St Joseph’s school by Mother Mary St Alban Coppock – but also at Blessed St Edmund Campion School in Iffley and Our Lady’s Junior School in Cowley during the 1970s.

Since Cherwell Edge was part of the OHS, the Oxford papers contain several letters from Grace Hadow who became Principal in 1920. One set of letters relates how the Police visited Cherwell Edge at the suggestion that poor men fed at the Convent had caused a disturbance in the neighbourhood. Although the officers admitted to Reverend Mother there was no evidence that the men helped by Cherwell Edge were linked to the trouble, the sisters felt they must give up their customary act of charity. Hadow sent a letter to her principles exonerating the sisters as she felt ‘I could not let such an attack on Cherwell Edge go unanswered’. In a letter to Reverend Mother St Theresa, Hadow praised the spirit in which the nuns dealt with these circumstances and stated, ‘I do most warmly appreciate the sacrifice you are making’.

Hadow’s letter to the Cherwell Edge sisters was written with genuine empathy since, like Butler, she had long been involved in social work. Both Hadow and Butler were prominent figures at Barnett House in Oxford, a centre for social research established in 1914 and precursor to Oxford University’s Department of Social Policy. Made secretary of Barnett House in 1920, Hadow worked with WGS Adams, one of its founders, to establish a series of schemes in rural communities to improve quality of life.

Hadow masterminded the village library scheme which inspired a further key project operated by Butler. With Charlotte Simpson, Butler taught local schoolteachers to make village surveys who would in turn encourage children and their families to observe and discover their surroundings ultimately becoming active advocates for the wants of their communities. Both projects achieved such success that they were replicated throughout the country and the world in countries colonised by Britain. Many of the local services we take for granted today can be traced to Hadow and Butler’s initiatives.

The Holy Child Settlement in Poplar, albeit in an urban setting, was a centre for clubs and evening classes that resembled many of the schemes which Barnett House sought to develop in rural Oxfordshire. A 1913 notice explains how Mayfield Old Girls had voted to take on the settlement after the death of its patron, the Duchess of Newcastle. Cooking, sewing and drill classes were already established and a number of old girls were chiefly involved with the popular club nights held there. In keeping with the musical spirit of the SHCJ instilled by Cornelia, two St Leonards old girls came once a week to play music for club girls to dance to.

The Annual General Meeting minutes for the Settlement show that the work supporting families and young people continued. In 1970, funds were given to three local boys who had achieved university scholarships as well as payment for wallpaper and paint for volunteers to decorate the homes of two families facing hard times.

From the arrival of SHCJ sisters at 14 Gate Street in London, the Society has long worked to improve the lives of those in poverty, through its core work of education and other ministries. Reminiscences and necrologies give accounts of acts of everyday kindness made by the SHCJ sisters. Sister Maura Healy was known for her generous spirit, giving sweet tea and sandwiches to ‘gentlemen of the road’ remembering how her mother never turned away a person in need at the door. Called to the SHCJ after her time as a domestic worker at Mayfield, however hard-pressed Maura was, she ‘always had time for a word with anyone who needed a prayer or some other service’.

Alongside teaching, Sister Helena (Lena) Brennan spent a great deal of her life working in deprived communities and finding ways to improve life for the people there. After many years teaching in the African Province, the Biafran War prevented her from taking up a new post in Nigeria. Lena used her time back in Ireland to take a MSc in Sociology, preparing herself for the social work she was drawn to. Returning to Nigeria, Lena was instrumental in the establishment of the Cardoso Community Project in Ajegunle, a densely populated and deprived area of Lagos. Sister Bernadette Okure, who continued Lena’s work as co-ordinator for the Project in 1980, described Lena as ‘bold and courageous’ in her work and a ‘pioneer’.

Lena went on to support Irish Travellers, living amongst the Clondalkin community as a witness to the injustices they faced. Over time, she saw the Traveller community grow confident in their own leadership. She then felt called to serve the people of Broadwater Farm, Tottenham, North London after the deaths of Cynthia Jarrett and P.C. Blakelock in 1985, when the estate was considered a ‘no-go’ area for social workers and police. Lena lived in a flat on the estate, to work with community workshops and be ‘simply here’. One resident of Broadwater remembered her as ‘like a second mother, loving all those around her, she was a rose in the thorn’.

SHCJ communities have established and been involved with many other projects to support those in need, such as the Salford Cathedral Centre created by Sister Kathleen King with the rest of the Salford Community in December 1989. Three years before, the Cherwell Centre in Oxford hosted an all councils’ meeting on ‘the meaning and implications of an option for the poor’. Here sisters reflected on their experiences and the history of the Society. Sr Anne Stewart reminded all attending of the following sentence from the SHCJ constitutions: ‘in Christ, we unite ourselves with the whole of humanity, especially to the poor and suffering’.

The fact that such a meeting took place in the very building where Violet Butler lived as she studied and engaged deeply with the needs of the people in her city, symbolises the SHCJ’s connection to a wider history of education and social reform. Struggles to bring about a just society and to provide a good quality of life for all have continued long after the work of Butler and the early SHCJ. Nonetheless, it is heartening to learn the stories of so many courageous women, willing to face such struggles to strive for the happiness of others.

Comments are closed.