15 November, 2022

‘We have become accustomed to Gunfire’: Sheltering in Hallfield’s Cellars during the Second World War

From the European Province Archives

Although most SHCJ schools at risk from air raids were evacuated during the Second World War – the children of St Leonards-on-Sea and Combe Bank were taken to Torquay and on to Hedsor Park near Maidenhead and Coughton Court in Worcestershire – both nuns and children living in the Holy Child School at Hallfield in Edgbaston, Birmingham sheltered in the cellar during both night and daytime air raids. Three volumes of the community’s Air Raid Diaries describe their experiences from 25th June 1940 until the 4th June 1943. The diaries give us a detailed impression of their routines moving to and from the cellar, installing bunk beds and ensuring all were safe while witnessing the War’s impact on Birmingham. Although there are moments of sober reflection upon the threat facing the people of their city, with true Holy Child Spirit, we can see how the nuns adapted to their situation and faced danger with compassion, patience and humour.

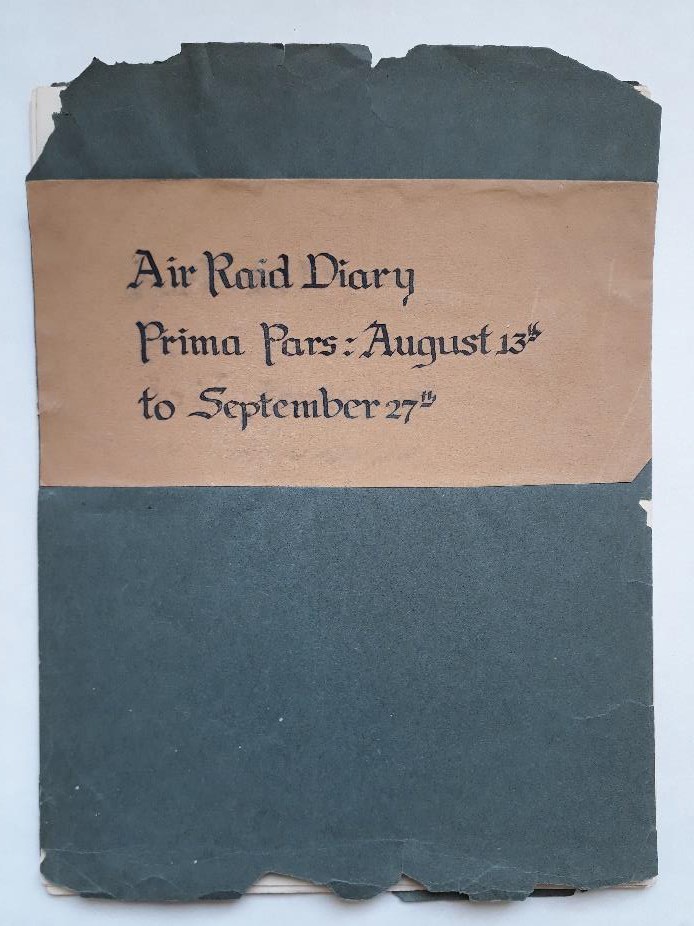

In neat script the title for the first volume of diaries reads ‘Air Raid Diary Prima Pars August 13th to September 27th’, reflecting the description of this early experience of wartime as a ‘noviceship’. The diary in fact begins a couple of months earlier. The first entry, Tuesday 25th June 1940 shows that the twelve children remaining at the school knew what to do when the alarm sounded. They were ‘quick in getting down with masks and blankets’. However, one of the nuns at ‘had to be called’. In subsequent entries, the speed in which both children and nuns come to the cellar and the names of those who had not come down immediately are noted along with a time for the air raid siren and the sounding of the all clear. This shows that the diaries had a practical purpose, assessing the effectiveness of the air raid procedures and perhaps noting which of the sisters slept deeply or could not adequately hear the sirens.

These practical details are not the only points covered by the diaries. The following Saturday, when all managed to gather in the cellar in five minutes, perhaps less familiar with the all- clear’s sound, Mother Maria Mercedes ventured up to check if the raid was over. At the convent gate, she heard the shout ‘warden’ and was told by the wardens that the raid had not ended at all. The diarist finishes her entry ‘So here we sit: we sing hymns “Hail Queen of Heaven”, “Sweet Heart of Jesus”, “Lord for tomorrow”, “Faith of our Fathers”.’

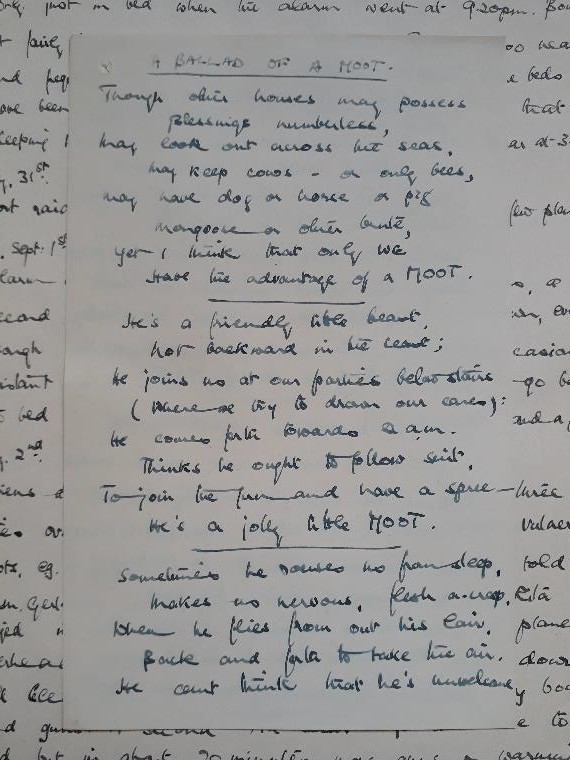

As the raids continued, the sisters made their cellar as a more habitable space and took plenty to occupy them. On the 12th September, supper was ‘taken hastily’ and afterwards ‘marvelous speed and shapes shown as the nuns appeared with trundles of shawls, blankets, books’. The preparation was soon needed as the sirens sounded at 8:10pm and the diarist again comments ‘here we sit, writing, reading, knitting, preparing lessons’. The entries begin to note that most of the sisters began to sleep through their time in the cellar as they grew more accustomed to spending their nights there. References are made to ‘the Moot’ a character waking the children and sisters in the night. This was evidently a rat banished by sisters ‘with raquet in hand’. He became such a familiar sight that the community decided to dedicate lines of verse to him and halfway through this first part of the diaries ‘the Ballard of the Moot’ is enclosed:

He’s a friendly little beast Not backward in the least;

He joins us at our parties below stairs

(Where we try to drown our cares) He comes forth towards 2am Thinks he ought to follow suit

To join the fun and have a spree

He’s a jolly little MOOT.

Such distractions and lightheartedness were sorely needed as the threat to the children and sisters came ever closer. On Monday 16th September a full account of ‘great activity in the air’ is given by the diarist who believes she heard ‘English planes

chasing the raiders’. She recounts ‘a flash- a whistling through the air and an explosion very near’. Soon after this came another explosion and the sound of gunfire. After this ordeal, the all clear was sounded at 11:40 and the children were given tea and biscuits in the kitchen before being sent back to bed. The sisters found out later that a bomb fell in a garden around 200 yards from the convent, with ‘every scrap of glass’ missing from nearby buildings.

This first volume of the Birmingham community’s air raid diaries ends with a summary of this period that offers a pragmatic assessment of how the sisters have coped:

we have systematized our vigils, having passed from the stage when we sat and talked through the hours of the night to a more settled horarium of reading praying and an effort to sleep.’

It also reflects on the impact of the war from the sisters’ perspective as they witness the destruction inflicted upon Birmingham: ‘we have grown accustomed to gunfire […] we have seen fires burning after the raiders have gone and the devastation in the city which daylight reveals’. Despite their hardships, a measured view is taken of dangers faced by the community themselves as the diarist stoically concludes ‘the war has visited us, but not very intimately’.

Sadly, the fear, uncertainty and restlessness of sheltering from deadly bombing raids is not a thing of the past, but a nightmarish situation faced by friends and family, neighbours and strangers seeking safety together during the war in Syria, the continuing war in Ukraine and other conflicts of the 21st Century. If we are to find some hope despite the tragic scenes and statistics bought to us in the news, it is perhaps in the striking similarity between how communities of all kinds cope with such fear and suffering: helping one another and singing, resting, laughing together.

Comments are closed.