19 November, 2025

At the beginning of October, I attended a meeting of the Catholic Archives Society’s Council held at St Mary’s Convent, Handsworth. St Mary’s has been a convent of the Sisters of Mercy since August 1841 when Catherine McAuley established Birmingham’s first post-Reformation community. The sisters went straight to work for the poor and gained the nickname of the ‘walking sisters’ as the people of Birmingham saw them venture out to visit impoverished homes across the city.

The CAS Council were given a very warm welcome by the sisters and Jenny Smith, archivist for Union of the Sisters of Mercy GB. Jenny also gave us a tour of this beautiful building designed by AWN Pugin in the heart of Handsworth. We saw their stunning chapel with its crucifix dating from 1846 and rescued from the neighboring St Mary’s Church that was destroyed in 1940. We also visited both their impressive heritage room and the cell where Catherine McAuley stayed during her last visit to St Mary’s. It was a real privilege to sit and eat in the same room where almost 180 years ago, Cornelia Connelly also received the hospitality of the Sisters of Mercy.

After a short-lived Hagley Road Community that lasted from 1881 to 1885, Mother Mary St Mark (b.n. Mary) Dallas and the Reverend Mother Provincial, Mother Mary of Assisi (b.n. Angela) Bethall, came to Birmingham to make a second foundation in 1933. Like me, both women found that their thoughts ‘naturally turned to another August nearly 70 years earlier’ when Cornelia arrived in Birmingham ‘a stranger without money, friends or experience.’

The SHCJ were requested to make a new foundation in Birmingham by the Archbishop. He was concerned by Birmingham’s wealthier families sending their children to either Edgbaston High School or the Church of England School for Girls since there was no equivalent Catholic fee-paying school. The SHCJ were to take over St Gabriel’s School which had been managed by the Sisters of Mercy for 20 years. Just as Cornelia was ‘received with great kindness by the Sisters of Mercy at Handsworth […] it was Handsworth that most of the sisters leaving St Gabriel’s were now to retire.’ When the Sisters of Mercy handed over St Gabriel’s in 1933, they left all the chapel furniture and vestments for the SHCJ and lent the chalice and ciborium ‘indefinitely’ while also recommending Mrs. Waltham to help clean the building. The Birmingham SHCJ’s house diary declared ‘during these days the kindness & consideration of the Sisters for the newcomers was unbounded.’ On 2nd September, the SHCJ took possession of St Gabriel’s.

From 1933 to August 1935, the SHCJ continued the original St Gabriel’s school. Luckily, the community had the assistance of Miss Duffy, ‘a former teacher who continued on our staff who proved to be a real “First Blue”.’ A short account of the SHCJ’s first years in Harborne noted how the sudden change was graciously accepted by children and parents:

The children showed a wonderful spirit. It must have been strange for them to arrive – many of them did not know of the change – and find not only different faces, but different habits, different methods etc. Thank God they took kindly to us and the parents too, soon became very appreciative of the work done in the school.

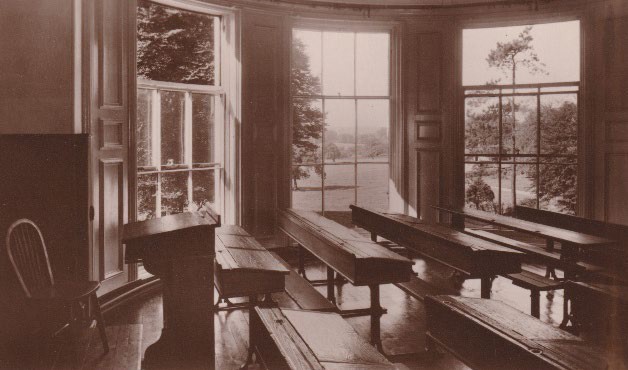

The Archbishop had shown ‘great interest and kindness’ in the SHCJ’s work but the school was sadly closed ‘as it seemed St Gabriel’s could never develop into the type of school his Grace wanted.’ As a suitable new property had not yet appeared, improvements were made to the existing building and a new school was opened on the same site on 23rd September 1935, the children ‘assembled in green uniforms’. The search for new premises continued nonetheless and eventually Hallfield on Sir Harry’s Road was secured. On 6th October 1936, the new term started at this grand and more accommodating site.

While the SHCJ were teaching at St Gabriel’s, they received visits from Father F. Gardner, chaplain to the Convent of Our Lady of Charity at Weoley Castle and friend of the Preston Community. From 25th February 1934, Sister Mary Immaculata (b.n. Rethna) O’Brien and Sister Mary Vincent (b.n. Margaret) Coupe went out to instruct children living in Weoley Castle and attending local council schools. Father Gardner discussed his project to build Weoley Castle School with the SHCJ throughout these early years as the annals and house diaries show. Four SHCJ nuns went to the laying of the school foundation stone on 19th October 1935. When the school opened on 24th July 1936, Mother Maria Mercedes (b.n. Mary Winifred) Maguire and Sister Mary Cecily (b.n. Hilda E.) Shepherd started as staff members.

Only three years into the progress of the SHCJ’s new school site in Edgbaston, Britain was at war. On the Feast of All Saints 1940, the Birmingham Community sent a completed community newsletter to the Province Leader. Relieved that there was no mention of SHCJ communities amongst lists of ‘nuns who have lost their lives’ in the Tablet, the Birmingham sisters based in the school and Convent in Edgbaston, felt to compelled to reach out:

Perhaps our desire to know is the real cause of this letter! Curiosity so often expressed led someone to suggest that we might write and give news of ourselves and maybe, in return hear how things were with you.

The Community reason in their letter that ‘compared with London of course Birmingham hardly knows that there is a War’ since bombing raids were comparatively shorter and less frequent. The community received Sister Christina (b.n. Louisa M.) Coles and Mother Mary Edmund (b.n. Audrey) Hemelryk in September 1939 as ‘refugees from Cavendish Square,’ along with Mother Mary Ignatius, who had arrived earlier, but eventually returned to London on 16th January 1940.

The annals record that the Birmingham community first experienced an alert on 5th September 1939. According to their October 1940 newsletter, at this time when the warning siren sounded ‘no one pays it any attention, though we have to notice it for the children when they are here and take them to the shelter’. The true impact of the ‘rather bad raids’ mentioned in the letter is described in fuller detail within the Community’s annals and air raid diaries. The annalist notes that 13th August 1940 ‘will ever be remembered as marking the beginning of Birmingham’s baptism of fire’ as long nights in the cellar began with a 11.45pm to 3.15am stretch. On 27th September, ‘two terrible bangs’ sounded at 7:45pm with bewildering effects – the curtains ‘blew in curves into the refectory’ despite the windows being closed. Those sitting at top table ‘felt as though they had been struck on the back.’ A few weeks after the nuns had sent their letter, Birmingham would endure ‘terrible’ nights on 19th and 22nd November when ‘thuds, bangs and explosions were continual’. During a raid of over 13 hours, many of the school and convent windows were broken and part of the Library ceiling fell down.

In September 1940, the cellars were adapted to accommodate both the nuns and the boarders. M.M. St Mark ordered mattresses and a carpenter spent a week erecting uprights for bunk beds while the doors of the old chapel and other materials were used to create beds. Although the longer nights of October 1940 meant longer raids ‘the school carried on as regularly as possible’, with lower line and junior children being taught in a cellar classroom during day raids while the Higher line stayed in the relative safety of the Montessori Room. Although numbers in the school dropped to 19 in January 1941, they increased to 31 children at the beginning of 1942 and by Michaelmas 1945, in the war’s aftermath, the number of was restored to 117 children.

Both the letter and annals note that ‘there were merry moments’. These include a nun dressing up in ‘a headdress like that of Miss Hewson’ and the ode written to ‘the Moot’, a noisy creature described as ‘half-owl, half-mouse’ by the annals who endures ‘innumerable proddings and bangings’. The community was encouraged by the sister-poet to ‘follow his indomitable example’. One night, a raid took place while the community and the Provincial, Mother Mary Paul O’Connor, were on a retreat led by Father John Bollard SJ. The community recalled how Fr Bollard joined the community’s ‘gay spirit’ while bombs fell and guns fired:

He was the essence of simplicity, talked and joked, said his office, slept and shelled peas – not very successfully! – for Sunday’s dinner’.

All such moments were recorded in both the letter and the annals as the community felt it was important to give a ‘glimpse’ of how ‘our nuns met the great strain’. In February 1941, the sisters divided themselves into four firefighting squads ‘as incendiary bombs were very fashionable at this time.’ They took turns ‘so that the rest of the nuns could stay peacefully in their beds.’

Three members of the Birmingham Community ventured out to a rest centre at Washwood Heath to provide food and support with Mrs Feeny. A letter by Mother Maria Josefa (b.n. Janet) Burke reporting on their work gives a bleak account of the impact of raids on Birmingham:

As we got out of the city and went towards Washwood Heath the devastation was simply indescribable. Whole rows of houses were demolished or burnt out in one street after another. Many big works, alas, were completely ruined – really one wondered how anybody could possibly have been left alive.

After ‘a great deal of palaver’, the sisters and Mrs Feeny were allowed by soldiers to drive past a bomb, but advised to keep well to the left of it. Mrs Feeny replied “It’s quite alright the sisters will say their prayers!” but they passed ‘before the sisters had time to think out even one prayer!’.

On their arrival at the rest centre, the sisters were swiftly involved in the busy work of providing relief. Sister Mary Cecily managed the tea urns ‘and kept us supplied as well as she could’ while Mother Mary St Agatha (b.n. Irene Jane) Howe ‘divided her time between cutting sandwiches and serving.’ M.M. Josefa describes herself ‘putting meat in a few sandwiches’, serving them out and answering ‘conundrums about lost rations and ration books, where to find clothing and whether it was possible to wash.’ M.M. Josefa was the first headmistress St Hubert’s School in Warley, Birmingham from 1937 and M.M. St Agatha was a teacher there, so the two were already used to working together as a team.

M.M. Josefa reflects that when the three sisters arrived home at Edgbaston ‘we realised that it had been hard work but I would not have missed it for anything in the world and I am quite sure that the others felt the same.’ She also praises the people they met on that day who had ‘a wonderfully magnificent spirit.’ M.M. Josefa concludes that ‘they made one ashamed for ever having grumbled or complained about anything.’ In a postscript, Mother Mary St Mark relates Mrs Feeny’s praise that the nuns ‘were splendid, in full work as soon as they arrived.’ A later manuscript note records that a lecturer on post-raid care told the story of three nuns whose ‘calm organization […] changed all! They were our three.’

The Birmingham Community became involved in an array of other works both related to the war effort and outside of it. Two nuns helped weekly at a Forces canteen and made beds at a W.A.A.F Hostel. From January 1943 to September 1946, the Convent also hosted ‘Sword of the Spirit’ courses for the R.A.F and W.A.A.F as well as Summer Leadership courses. Attendees in 1943 ‘loved the course and the convent atmosphere’ and the annals noted ‘we all feel it has not only been a pleasure, but also a privilege to help in so good a work.’

The Nurses Guild held meetings at the Edgbaston Convent from 1941 onwards. A girl guide company was set up in 1943 and the children from Weoley Castle school had their sports day at Edgbaston school on Ascension Day 1944, sang Benediction in the chapel and performed ‘Alice in Wonderland’ to raise funds for the school.

To close this article, I will leave you with the words of the sister writing on behalf of the Birmingham Community in 1940. During a time of both difficulty and danger, she states that it was the Society’s bond which helped them pull through:

We are much comforted ourselves in these crucial days by the strong bond which unites us all and, though we hear so little of each other, we somehow feel the support which this gives.

This article was originally intended to also cover the SHCJ’s post-war ministries in Birmingham, but accounts of the sisters’ war time experiences proved to be so absorbing that the decision was made to split the history into two parts. The second part will look at how the Society’s spirit of unity extended to the SHCJ’s neighbours and friends in Birmingham.

Comments are closed.